- Home

- Sally Mann

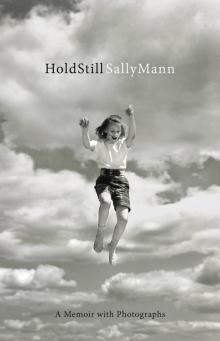

Hold Still Page 2

Hold Still Read online

Page 2

John Brown was gazing south from the northernmost, and widest, part of the valley, but had he been standing on the scaffold in our part, some 150 miles south, his wonderment and fustian would have been tenfold. Everyone’s is, even without the scaffold and the imminent hood. Had Brown been in Rockbridge County, he would have begged the hangman for one more minute to experience the geologic comfort of the Blue Ridge and Allegheny mountain ranges as they come together out of the soft blue distance.

This effect is especially apparent as you drive down the valley on I-81, the north-south interstate that parallels I-95 to the east. As you approach Rockbridge, the two mountain ranges begin to converge, forming a modest geographic waist for the buxom valley. By the time you cross the county line, neither of them is more than a ten-minute drive in either direction.

If that weren’t enough extravagant beauty for one medium-sized county, then shortly after crossing into Rockbridge you are presented with the eye-popping sight of three additional mountains: Jump, House, and Hogback. Responding to Paleozoic pressure, this anomalous trio erupted like wayward molars smack in the central palate of the valley, each positioning itself with classical balance, as though negotiating for maximum admiration. When they come into view at mile marker 198.6, occasionally radiant with celestial frippery, you will stomp down on the accelerator in search of the next exit, which happens to be the one for Lexington.

I had the good fortune to be born in that town. In fact, even better, I was born in the austere brick home of Stonewall Jackson himself, which was then the local hospital. Due to overcrowding, I bunked in a bureau drawer (maybe Jackson’s own?) for the first few days of my life. And when I was a stripling I rode my own little sorrel, an Arabian named Khalifa, out across the Rockbridge countryside just as Jackson did. I could ride all day at a light hand gallop through farm after farm, hopping over fences oppressed with honeysuckle and stopping only for water. Much of that landscape is now ruined with development, roadways, and unjumpable fencing, but the mysteries and revelations of this singular place, just as I observed in my earliest journal entries, have been the begetter and breathing animus of my artistic soul.

2

All the Pretty Horses

Except for a stretch in the middle of my life, horses have been either a fervent dream, as these childhood drawings attest,

or a happily realized fervent passion. To write about how important place is to me, especially in my life with Larry Mann and in my photographs, I have to address how essential horses have been to it as well. Larry and I had three often cash-strapped decades when we had no horses in our lives, between our marriage in 1970 and our move thirty years later to our farm. But all that time my buried horse-passion lay still rooted within me, an etiolated sprout waiting to break greenly forth at the first opportunity.

And when at last that opportunity came in the spring of 1998 and Larry and I acquired our family farm from my older brothers, Chris and Bob, I bought the first horse I could find. With the purchase of that spavined old (re-)starter mount, my dormant obsession burst into full, extravagant leaf.

I’ve been said to be temperamentally drawn to extremes, in good ways and bad, and part of what I love about the kind of riding I do is the extreme physicality of it. Appropriately called “endurance riding,” the sport entails competitions of thirty, fifty, and one hundred miles, going as fast as you safely can and almost exclusively on tough little Arabian horses just like Khalifa.

The landscape through which we race is usually so remote it is just the horse and me for dozens of fast and sometimes treacherous miles, an elemental, mindless fusion of desire and abandon. Sometimes we are running alone in the lead, and at those times I can’t deny the observation of the writer Melissa Pierson that nothing may be fiercer in nature or society than a woman gripped by a passion to win. Nothing, that is, except a mare so possessed.

And in those moments I am wowed by the subtle but unambiguous communication between our two species, a possibility scoffed at by those unfortunates who haven’t experienced it, but as real and intoxicating as the smell of the sweating horse beneath me. That physical and mental bond—the trail ahead framed between my eager horse’s pricked ears, and the ground flying under her pounding hooves—can reset my brain the way nothing else does and, in doing so, lavishly cross-pollinates my artistic life.

This riding rapture, so essential to my mind and body, would never have been possible, and my slumbering horse passion would have remained buried and unrealized, were it not for our farm. And not just that: without the farm, many of the other important things in my life—my marriage to Larry, the family photographs, the southern landscapes—might never have happened either.

On our fortieth wedding anniversary, in June 2010, I received this email from our younger daughter, Virginia:

Although you have said you don’t want to make a big fuss about this, I think you are both proud of what you have achieved today: it is a testament to love, to a commitment to equality, patience, selflessness and, of course, the farm.

How odd it is that a piece of land should figure so prominently into her concept of our marriage, and yet how perceptive and accurate that observation is. Even before Larry and I met, in December 1969, our farm had been the setting for an Arthurian pageant of predestination, set in the aftermath of an epic flood.

In August 1969, Hurricane Camille rolled into Pass Christian, Mississippi, where she hit with Category 5 intensity, then made her way northeast and crossed the Appalachian Mountains into the Shenandoah Valley. Picking up moisture from heavy rains in the previous days, Camille dumped a staggering twenty-seven inches of rain in three hours onto the mountain streams that drain into the Maury River, the dozy midsized waterway that loops around our farm.

Our cabin on the Maury, built well above any existing flood line, was clobbered by a wall of water carrying logs, parts of buildings, cars, and detritus of every imaginable kind. The water reached the roofline, but a large hickory prevented the cabin from joining its brethren headed a hundred and fifty miles downstream to Richmond. As the flooding diminished, leaving angry snakes, a poignantly solitary baby shoe, tattered clothing, splintered wood, and nearly a foot of sand on its floor, the cabin subsided more or less where it had been before.

My parents wearily began shoveling out the sandy gunk, noting the many treasures washed away by the floodwaters. Most vexing was the loss of the large entry stone, concave like an old bar of soap, that had memorably required several men to put it in place at the cabin’s 1962 christening. Believing such a rock could not have been swept far, my father eventually located it under a mound of debris and shoveled it free. But he needed some help to move it back to the doorway, so he called my W&L boyfriend, who offered to come with his strong friend, Larry Mann. The three of them rode out to the farm on a fall afternoon in my father’s green Jeep.

Apparently, the rock’s smooth surface made it difficult to grip and several times it nearly mashed their toes. After one particularly close call, Larry asked the other two to stand back and, in a moment I imagine as bathed in a focused beam of mote-flecked sun streaming through the tree canopy, hoisted the rock onto his back.

My father and boyfriend surely stood openmouthed… no, indeed, in my mythically heroic replay, I am sure they knelt, shielding their eyes as they gazed up at the epic vision of luminous Larry Mann replacing the threshold stone.

But in prosaic truth, lusterless Larry staggered to the cabin with the stone barely atop his back and unceremoniously dumped it in reasonable proximity to the door, panting with the effort. Still, even without the imagined heroism, my boyfriend said that when he glanced over at my father he was startled to see him looking at Larry with a bright gleam of acquisitiveness in his eye. Certainly it was more than just satisfaction at having the stone back in place. My boyfriend said he knew right then that the result of this portent-laden moment was that Larry Mann would be marrying my father’s daughter.

And here is where the horses come back in. One o

f the tenuous links that my childhood had with Larry’s was that we both rode and loved horses. Without this link, my father’s marital hopes for his daughter might never have been realized. But, like so much of his childhood, Larry’s riding experience was a world apart from mine.

There’s a certain horse culture to which I yearned to belong when I was young—the culture of grooms, bespoke boots, imported horses, boozy hunt breakfasts, scarlet shadbellies, and grouchy, thick-bodied German instructors biting down on their cigars. This was Larry’s horse world.

Mine, more passionate and far less structured, revolved around a Roman-nosed plug and her companion, a bright chestnut Arabian yearling given to my father, a country doctor, in return for a kitchen-table delivery. The former was misnamed Fleet and we named the colt Khalifa Ibn Sina Demoka Zubara Al-Khor, which classed him up a little. There were no grooms to clean the boggy lean-to that housed this unlikely pair, I rode without a helmet in Keds sneakers and untucked blouses with Peter Pan collars, and I never had a real lesson.

At first I didn’t even have a saddle, as my parents assumed that if they made it miserable enough, this “horse-crazy” phase would pass. But I stuck with it, riding that old mare bareback, her withers so high and bony they could serve as a clitoridectomy tool. After six months of this, I decided that the nicely rounded back of the little Arabian colt looked awfully appealing.

So, one day I climbed up on the eighteen-month-old youngster who hadn’t had the first moment of training, and off we rode, a rope halter my only means of control. As one might imagine, Khalifa taught me the only thing I ever really needed to know about riding, and perhaps about life: to stay balanced. Never mind the heels down, the pinky finger outside the rein, or mounting from the left. This little red colt taught me how to ride like a Comanche.

And that’s what we did, flying hell-bent-for-leather across the nearby golf course, which my socialist-minded parents had taught me to disdain, sailing over barbed-wire fences and, when the heat softened the asphalt, racing startled drivers on flat stretches of the road. I rode Khalifa every day and, in a preview of my later miscreant teenage behavior, would set my alarm to ring under the pillow and climb out the window to ride under the wild, fat moon.

My parents, despite my obvious joy in riding, still refused to support it. I understand their indifference, or perhaps it was something stronger—disapproval. They were intellectuals; they hung out with artists and academics, not horse people. The thought of my proper Bostonian, New Yorker–reading mother resting her spectator pump on a muddied rail and chatting up a neatsfoot-oil-smelling horse mother is almost impossible for me to conjure. So antithetic is that notion that even then, when I suffered their indifference most painfully, I didn’t particularly resent it.

It would suit this narrative if I were to tell you that my mean and insensitive parents sent me to boarding school in the snowy north to separate me from my true love, Khalifa. But the truth is this: my confused and concerned parents sent me to the snowy north (that part is still true) because my reckless behavior on horseback had morphed into reckless behavior in other areas. The biggest threat to a young equestrienne is not the forbidden bourbon from the flask on the hunt field or a foot caught in the stirrup of a runaway horse. It is, of course, boys.

My first horse chapter ended badly. When I left for boarding school, my father shuffled Khalifa and Fleet out to the farm where they apparently harried the cattle belonging to a tenant. This cowpoke called our house one night and, with a bumpkin persuasion that could charm a snake into a lawn mower, convinced my father to give the horses to him for riding. Within a week he sent the old mare to be killed at the meat market. When we discovered this, I went in search of my fine little sorrel Khalifa, tracking his dwindling fortunes as he went from one horse trader to the next in Black Beauty–like abasement, before ending up, like the mare, as dog food.

3

The Bending Arc

As many people have remarked, I am lucky to have found Larry Mann when I did. Whether I was born this way or my personality was formed by circumstance, I don’t think anyone would call me an easy person to deal with, and by the time our paths crossed, the hormones of the teen years had only made things worse.

I had been a near-feral child, raised not by wolves but by the twelve boxer dogs my father kept around Boxerwood, the honeysuckle-strangled and darkly mysterious thirty-acre property where I grew up. The story of my intractability has been told and retold to me all my life by my elders, usually accompanied by a friendly little cheek pinch and a sympathetic glance over at my mother. Recently, in tracking down stories about Virginia Carter, the black woman who worked for my family for nearly fifty years, I visited Jane Alexander, a ninety-six-year-old who repeated to me, in a soft voice with a bobby-pin twang to it, the now familiar tale of my refusal to wear a stitch of clothing until I was five. Family snapshots seem to bear this out.

I know that my mother tried to raise me properly, but I made her cross as two sticks, so she turned the day-to-day care of her stroppy, unruly child over to Virginia, known to everyone as Gee-Gee, a name given her by my eldest brother, Bob. Jane Alexander reminded me about the beautiful, often handmade dresses that Gee-Gee would lovingly press for me, in hopes that they would soften my resolve to live as a dog. I have them still, pristine and barely worn.

If my early years sound a bit like those legends of wolf-teat sucklers, I guess they were. But, all the same, when I compare the lives of children today, monitored, protected, medicated, and overscheduled, to my own unsupervised, dirty, boring childhood, I believe I had the better deal. I grew into the person I am today, for better or worse, on those lifeless summer afternoons having doggy adventures that took me far from home, where no one had looked for me or missed me in the least.

Looking back, though, it could be that my parents were a bit on the less-than-diligent side, even for the times. Once, when I was with my mother in the dry-goods section of Leggett’s department store, we saw the distinctive going-to-town hat worn by Mrs. Hinton bobbing above the bolts of cloth. She was the mother of my brother Bob’s best friend, Billy Hinton. When she saw my mother she brightened and said, “Oh, Billy just received a postcard from Bob. Apparently he loves his new school!”

My mother, rubbing some velveteen between forefinger and thumb, responded distractedly, “Oh, that’s good, we hoped he had gotten there okay.”

Turns out that ten days before, my parents had packed a steamer trunk full of warm clothes for my fifteen-year-old brother and driven him to the Lynchburg, Virginia, train station. After eight hours on the Lynchburg train, he had to change stations in New York. My parents told him to carry his trunk from Penn Station to Grand Central and to locate the overnight train to a town near the Putney School, the Vermont boarding school he was to attend. Then they left him and apparently never wondered if those connections had worked for the boy, who had not traveled alone before, or even if he had made it to Putney at all. They had heard nothing since dropping him off and had never called the school to check.

My mother told that story countless times, laughing gaily at her recollection of Mrs. Hinton’s shock.

The assumption back then, in the palmy, postwar Eisenhower years in America, was that everything was fine now—and that was true, for the most part. I think my parents were fairly untroubled by child-rearing issues, except for the constant battles over clothing their stubborn hoyden; my father called me “Jaybird” because I was that naked. But eventually even that was solved by the arrival, in 1956, of Mr. Coffey’s carpentry crew, there to build a cottage for my grandmother Jessie on the property. My mother proposed a deal: if I wanted to hang out with the carpenters, I had to wear clothes of some sort. I was so lonely I took it.

Even though I finally agreed to wear clothing, I had some difficulty working out the details, as my mother’s exasperated journal entries report.

Despite being kicked out several times for not wearing any underwear, never mind tattered and dirty, a few mornings

a week I began to attend Mrs. Lackman’s preschool, where I worked on my socialization skills. By springtime, I had managed to make some human friends whose parents drove them out to my house for a birthday party presided over by Gee-Gee.

By the time I began real school, I was almost normal: I no longer spent my days poking at snapping turtles in the pond, or hiding out with my grubby blanket in my honeysuckle caves, or following my unneutered beagle on his amorous adventures down the paved road, from which, when I was hungry, I would pull stringy hot tar to chew like gum. I now wore crinolines, little white socks, and gauzy dresses.

I joined the Brownies

and the Episcopal Church choir.

But look closely: if you study the choir picture, something is still not quite tamed in the child pictured there.

And what is this? What is in those Brownie eyes?

If you had to judge by my average test scores, I suppose it’s not raw intelligence you see in them. I was always a pretty bad test taker, especially so where math was concerned.

Hold Still

Hold Still